I wrote an ode to magnolia trees, but not just any tree—The Queen of Gambier, Ohio! To find out more, pick up a copy of Field Notes from the Brown Family Environmental Center, or many locations around the Kenyon College Campus, or just read the full essay here.

The Queen of Gambier

When I arrived this summer in Gambier to join Kenyon College’s incoming faculty, one of the first things that I noticed was the abundance of stunning trees. Admittedly, I am a tree nerd, fitting with my position here as a science and nature writer, but the trees of Gambier seemed more majestic than I had imagined. I should have been able to predict—the school has been around since 1824, and Ohio is a verdant landscape home to a wide range of species, so why would the trees be any less impressive?

I spent my first few days settling in and exploring all corners of campus, identifying as many species as I could, and making note of particularly charismatic trees. I asked everyone I met if they had any favorites, and without fail, every single person mentioned the “Upside-down Tree”—the weeping beech behind the Chapel, and although I am equally enamored with that wizened, magical specimen, I will save that tree for another essay; my loyalty rests elsewhere. I found myself infatuated with a tree that is hidden on campus, but no less remarkable. On the corner of West Brooklyn Street and Ward Street, between the Davis House (Anthropology) and the Treleaven House (Sociology), there is a jumbled patch of trees, all various species, sizes, and ages, and in the middle stands a tree that struck me as dignified, from her crown-like ring of basal branches to her glowing red fruits, and so from here on I will refer to her as the Queen. This tree has flowers that are alternately referred to in botany as perfect, bisexual, or hermaphroditic—these terms are synonymous, so I will simply explain that perfect flowers contain both staminate and pistillate parts. Thus—my use of the nickname ‘Queen’ and female pronouns is purely based on the vibes that I get from this tree, not based on any scientific data. It’s her mood, her look, her overall persona.

Her leaves are huge—longer than my arm and wider than my head—one leaf that I plucked measured two and a half feet long (30 inches) and a foot wide. Each leaf is obovate, or oblanceolate if you’re going to get nitpicky; broadest distal to the middle of the leaf. The upper surface of the leaves is a vibrant green, and the underside is whitish, soft, and slightly hairy. The midrib is thick and pale green, and the veins emerge pinnately along it. The stipule is quite thick. Forgive me—I’m going to continue with a few more technical descriptors, but you’ll soon learn why I’m going into so much detail. The leaves are simple and entire, yet they are clustered together towards the end of the stem, giving the illusion that they are leaflets in a palmately compound leaf, but don’t be fooled—the axillary buds present at the base of each leaf help you to see that they are not. As a group, their arrangement forms a little dome, resembling an umbrella of leaves, thus the common name umbrella magnolia.

Here’s where things get tricky. I am an amateur botanist; my training is in creative writing and my botanical tools are still in the process of being sharpened. I often rely on books, as well as crowd-sourced, community science tools, such as the app iNaturalist, which allows you to upload photos of flora and fauna seen in the wild, and once you enter the location data and photo, the AI technology allows you to compare and contrast your observation with photos that appear similar. Your selection can then be verified by other community scientists including taxonomic experts. Using this tool, I surmised that this particular tree is an umbrella magnolia, Magnolia tripetala L.

Several days after my ‘discovery’, I spoke with David Heithaus, Kenyon’s Director of Green Initiatives. He agreed with my identification and mentioned to me that as far as he is aware, this is the only tree of its kind on campus, technically, although there are a few other umbrella magnolias in the woodlot down the hill from the studio art building. He gave me verbal directions to “Sunset Point,” an overgrown trail with a few precarious stone steps that lead into a sloped forest. I explored this trail and found three or four trees that could possibly be juvenile or growth-stunted umbrella magnolias, none as grand as the magnolia on Brooklyn Street. Until I am proven wrong, I am going to celebrate “my Queen” as the only umbrella magnolia on campus proper. However—a few factors give me pause to my confidence. First of all, after checking out every tree guide I could get my hands on from the Chalmer’s library, I read several conflicting accounts about magnolia species. In the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees, Eastern Region, the umbrella magnolia (Magnolia tripetala)is described as having leaves ranging from a length of 10 to 20 inches, whereas the bigleaf magnolia, Magnolia macrophylla, is described as having leaves ranging from a length of 15 to 30 inches, found in many regions including Ohio, while the umbrella magnolia is most often found in southern states. In A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America, a similar measurement is described of 18 to 20 inches long leaves for umbrella magnolia, in comparison to 20 to 30 inches for bigleaf magnolia. What gives? The tree on Brooklyn Street in Gambier has many leaves in the 20 to 30 inch range, and even a few that exceed 30 inches. To complicate the matter further, when I met with Andrew Mills, the current grounds manager at Kenyon, he and several of his coworkers insisted that the Queen must be a cucumber magnolia.

I went back to the intersection of Brooklyn and Ward to investigate, and I decided to take a casual survey of all the trees on the block, starting with the Queen, and radiating outward in a loose spiral. I am delighted to report that the copse of trees on that corner is surprisingly diverse: in a fifteen-foot radius, I found a larch, a sycamore, a mulberry, a hop hornbeam, a rhododendron, a black locust, a black cherry, a white pine, an oak, a fir, a red maple, an old field apple tree, a horse chestnut, a hemlock, a sawtooth oak, a catalpa, a viburnum, and what appeared to be another magnolia tree. With a quick examination, I found that this other magnolia is more likely to be a cucumber tree, Magnolia acuminata. It has much smaller leaves, averaging about 7 to 10 inches in length. So here is the cucumber magnolia that Andy Mills and his coworkers must have been thinking of, or maybe as a newcomer I simply described my locality wrong.

The mystery remains about the tree field guidebooks—is the Queen a bigleaf magnolia or an umbrella magnolia? I did some deeper digging into the morphological differences between the two species, and I found the possible answer to the question: bigleaf magnolias have two rounded lobes at the base, like little earlobes. The Fraser magnolia also has a heart-shaped or lobed leaf-base, but the umbrella magnolia does not. Not one of the Queen’s leaves are lobed at the base. So—even though the Queen’s leaves are ten inches longer than the reported length of umbrella magnolia leaves described by all sources, I can at least rule out the cucumber, Fraser, and bigleaf magnolias. The only other magnolia species that approximates this leaf length is the Ashe magnolia, Magnolia ashei, which is only found in Florida.

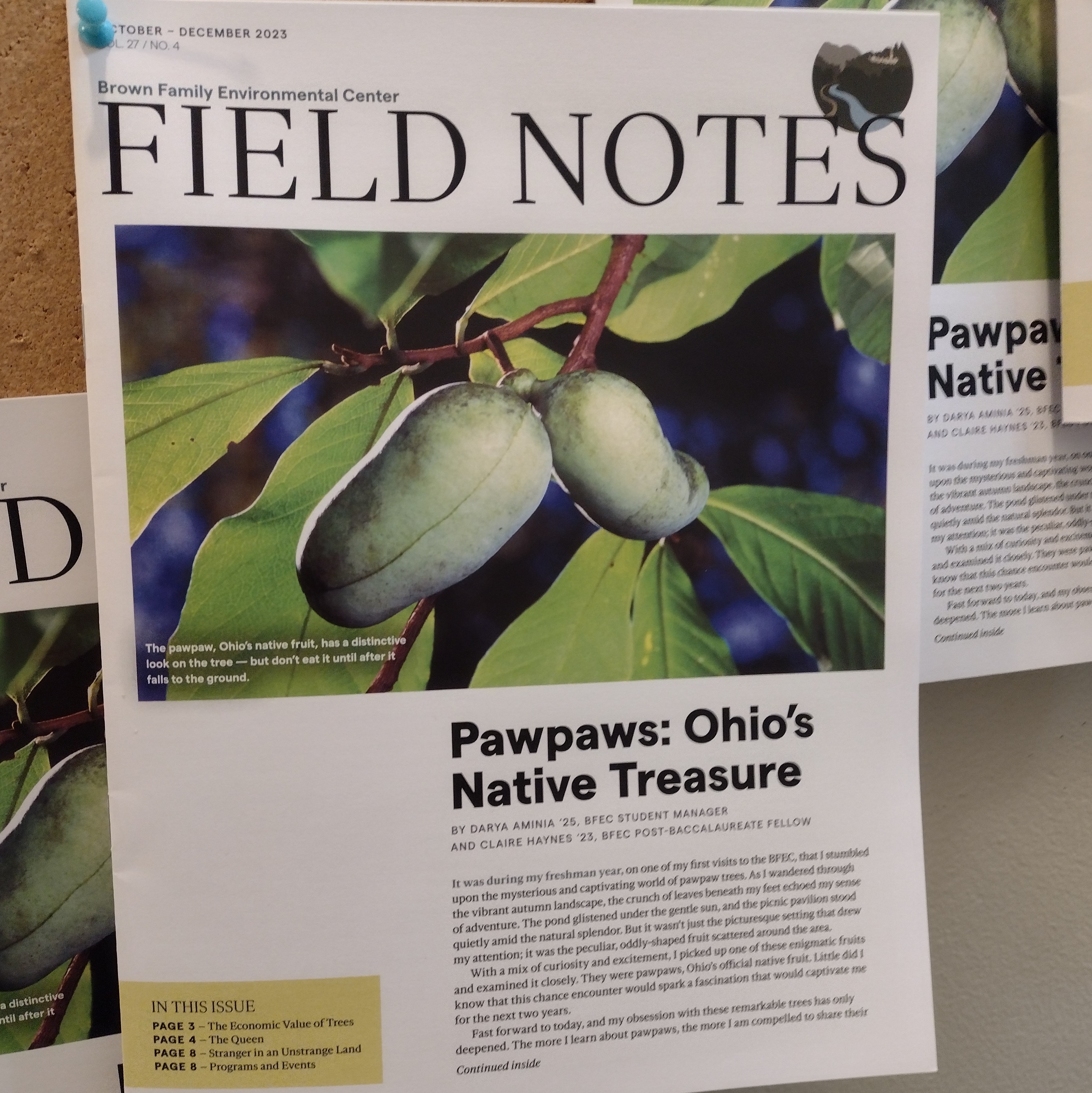

I have not yet described the fruits of the Queen, which are similarly notable and unique. In this season that I am writing this piece, late August/ early September, the fruits are still a pale pink, four to six inches in height, two to three inches in width. If you have not yet examined a magnolia fruit, you’re in for a treat. They’re conelike, but also alien-blob-like. They’re fleshy and thick until they crack open to reveal bright red seeds that pop out from the fruit’s carpels.

Keep an eye on the Queen’s flowers in the spring, for the flower of any magnolia tree is a sight to behold: often, from species to species, they are cup or candle-like in appearance; white petals pointing skyward as if in prayer, and offering strong aromas to any passersby or pollinator. Since I have only just moved to Gambier, I missed the spring blooms of the Queen, and I will have to wait until next year to report back on the vision and scents of her blooms. Unfortunately, all of the guidebooks that I read describe her flowers as unpleasant or disagreeable. Donald Culross Peattie, author of the aforementioned A Natural History of Trees, describes the Umbrellatree as elusive, rare, beauty-dispensing, and unforgettable, but also in these magical terms. Keep in mind that this book was written in 1948,

“As you tramp or motor beside the roaring streams of Great Smoky Mountains National Park in May, the Umbrellatree, with its big, creamy-white flowers, repeats itself over and over, until the forest—made up of the most magnificent hardwoods of the North American continent, seems populated by a troop of wood nymphs.”

If you’re not yet convinced that the Queen is a notable tree on campus, consider how neat magnolias are in general. Magnolias are an ancient group of plants; their fossil record dates back 95 million years. Magnolias are often considered to be among the earliest known angiosperms, or flowering plants. The primary pollinators of magnolias are beetles, although other insects visit as well. The beetles and trees have a unique relationship that may indicate a concurrent, symbiotic evolution, or ‘pollination syndrome’: the flowers have lots of ‘parts’, i.e. lots of petals, lots of stamens, and lots of pistils, in comparison to other angiosperms, and beetles often feed on the stamens as part of their visit. Many species of magnolia produce floral heat and scent at night which entices the beetles to spend the evening in their warm embrace, feeding on their anthers and spreading pollen onto their stigmas.

[This could be a possible place to split the essay in two, although I’m not certain about the continuity]

Perhaps what is most compelling about the Queen isn’t her enormous leaves, her vivid red seeds, her beetle-pollinated stinky flowers, or that she is the only representative of her species on campus (if you exclude the juveniles in the west-facing woodlot), but rather her community on the corner of Brooklyn and Ward. In my casual tree survey of campus, I have not yet encountered such a dense and species-rich grove of trees. Their arrangement almost seems accidental and chaotic—they’re all close together, and most of them are the only individual of their species on the block. They appear to be in conversation with one another, as though the trees are having a slow, decades-long cocktail party. If you walk around campus with the intention of identifying tree species, you won’t find the same type of chaos as on Brooklyn and Ward. In general, you will find trees to be spaced out evenly, and most trees will have companions of the same species nearby: oaks with oaks, maples with maples, and so on.

The historical record of trees at Kenyon College is slim. Elizabeth Williams-Clymer, a librarian in Special Collections, helped me track down a few odds and ends, including tree bulletins from 1910, 1912, and 1914. These bulletins were all published by the “Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station,” as reports on forestry operations and woodland conditions. The 1910 bulletin describes the Kenyon forest, comprising about 200 acres, some of which contains a “fine, virgin stand of oaks,” as well as new plantings of walnuts, dogwood, hickory, and red maple. The 1912 bulletin describes a planting event of “3,700 tulip poplar, 600 white ash, 100 bald cyprus, 1,750 white pine, 300 Norway pine, 1,080 Norway spruce, 200 Austrian pine, 1,500 red oak, 100 burr oak, 200 European sycamore, 175 American sycamore, 600 linden, 230 chestnut and 210 red mulberry.” The 1914 bulletin makes a few updates, including a continued planting effort: “300 pines, 900 chestnuts, and 2100 red oaks” while “a mature stand of black and white oaks were removed”. Sadly, I believe most, if not all, of those chestnuts are gone, due to a mass blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, which began in 1904 and ravaged the North American population of chestnuts.

It’s difficult to know how many of the trees listed in these bulletins still remain, if any. Heithaus mentioned to me that a grand old white oak was recently cut down to make way for a parking lot, bringing to mind the Joni Mitchell lyric, “they paved paradise, and put up a parking lot.”

Williams-Clymer also pointed me towards a 1983 tree survey, which is currently kept down in the Maintenance offices. Andy Mills, the Kenyon College grounds manager, loaned me the dense survey, which I spent several evenings attempting to decipher. The survey doesn’t come with a map, only reference to tree tags, which of course are often missing, swallowed up in the tree bark or chewed on by squirrels. It is useful, however, to see the distribution of species, and to note that in 1983, there were at least 2,060 on campus, the most common trees species that year seem to be oak, maple, hickory, black walnut, pine, honey locust, and arborvitae. Less common species, and therefore more thrilling to me, are catalpa, tulip poplar, larch, sassafras, ginkgo, mulberry, persimmon, tupelo, and Kentucky coffee tree. There are, sadly, many ash trees listed in the survey, while today, thanks to the nasty ash borer, there are only a few remaining. There are also many elms listed—the majority of which were likely destroyed by Dutch elm disease, although Heithaus says, “I’d be shocked if we didn’t have some slippery elms or Chinese elms around. Knox county got hit pretty hard by Dutch Elm.”

Many of these trees have been cut down due to storm damage, disease, or to make space for new construction. I spoke with several colleagues who are still mourning the loss of specific trees which were cut down for parking lots, the library, and the new dorms. Up until recently, Kenyon College held a ‘Tree Campus USA’ certification which has lapsed due to many recent construction projects and cuttings. On a lighter note, I was happy to learn that all the ‘deadwood’, including branches and trimmings, are recycled into mulch that is used in the landscaping on campus and at the farm, so in that sense—no tree is ever truly gone from campus. The trees also linger in local memory despite their absence; I have heard several colleagues and students refer to the missing trees as ‘ghost trees,’ some of the many ghost stories of Kenyon College.

The ’83 survey has no mention of the Queen—I read through the entire survey twice, scanning for an umbrella magnolia, and no luck. The survey mentions a bigleaf magnolia, which I have not yet seen on campus, and many cucumber magnolias, which of course have smaller leaves, and I’ve found a few of these scattered around campus, particularly the glorious specimen between the Kenyon Review house and the Kenyon Inn. Perhaps the Queen was planted after 1983, although her girth would suggest that she is older than 40 years of age.

After reading through all these old surveys and records, I finally found the true font of tree knowledge: Steve Vaden, Kenyon’s former Grounds Supervisor, recently retired, who kept a careful eye on all of the trees on or near campus for more than two decades. We met at Wiggins Street Coffee and Vaden shared enough tree stories to fill a book; it is so often the case that these invaluable oral histories don’t make their way into the institutional archive. Steve finally cleared up the Queen’s background for me. Lewis Treleaven, who worked for the college in many positions and was named Gambier Citizen of the Year in 1989, planted many of the trees on the corner of Ward and Brooklyn when he occupied the house. He sold the Treleaven house to Kenyon in 2002, and passed at the age of eighty-nine in 2008, so alas—I can’t ask him about the Queen’s origins. Vaden, however, seemed to know a lot about the Queen; he described how she might have been planted in the 80’s, and has gone through some tough times since, including many hard frosts during which she ‘died back to the rootstock’, explaining why she has multiple trunks in a ring formation surrounding what would have been the original stem.

Soon after I began to write this piece, I biked by the intersection to examine the Queen’s leaves more closely, and as I approached, I was horrified to see three or four maintenance vehicles parked along Brooklyn Street. I saw that parts of the lawn adjacent to ‘my tree’ had been marked with colorful tags and wooden posts. Were they about to chop her down? I lingered for a few minutes to surreptitiously assess their project, and with relief, I realized that they were simply building a sidewalk parallel to the road. I hope that in all the new construction and expansion of Kenyon College, that this tree and all her tree companions on the corner of Brooklyn and Ward, will be celebrated and spared. Please pay her a visit, write an ode, paint her portrait, and spread the word of her glory across campus and beyond.